Admit it. You’ve all experienced that mind-numbing exercise of having to read a certain book. “It’s a classic, a pillar of our literary canon,” gushed the teacher while shoving one of August Strindberg’s works in our hands. (Swedish literary canon, obviously.) Or you were handed a dog-eared copy of 1984 and told this, this was manna for the soul. (I much preferred Animal Farm. “All animals are equal but some animals are more equal than others.” A quote that, sadly, is as applicable today as when Orwell first wrote it)

Thin g is, even classics become dated. In fact, sometimes they become irrelevant, because the reality they describe is too far removed from the world that surrounds us. Over time, all classics essentially become historical fiction, and many readers don’t want to read about the past., they want to read about the here and now. This, I believe, is especially true of teenagers who are probably struggling with hormones and finding themselves just as a helpful soul gives them The Old Man and the Sea to read. Don’t get me wrong: I think this is a great book. Now. I wasn’t that taken with it as a fifteen-year-old, because seriously, an old man fighting a big fish became a bit old after the first ten pages or so. At the time, I wanted to read stuff that somehow reflected my own, very confused, reality. No fish or old men figured in my teenage daydreams…

g is, even classics become dated. In fact, sometimes they become irrelevant, because the reality they describe is too far removed from the world that surrounds us. Over time, all classics essentially become historical fiction, and many readers don’t want to read about the past., they want to read about the here and now. This, I believe, is especially true of teenagers who are probably struggling with hormones and finding themselves just as a helpful soul gives them The Old Man and the Sea to read. Don’t get me wrong: I think this is a great book. Now. I wasn’t that taken with it as a fifteen-year-old, because seriously, an old man fighting a big fish became a bit old after the first ten pages or so. At the time, I wanted to read stuff that somehow reflected my own, very confused, reality. No fish or old men figured in my teenage daydreams…

Not all classics become dated. As an example, Robinson Crusoe is still very readable. As is Tom Sawyer, Anna Karenina and Crime and Punishment (although veeeeery long and rather depressing). Or Lord Jim, Kristin Lavransdotter, Great Expectations, For Whom the Bell Tolls, Jane Eyre—the list is actually quite long. (And must include The Little Prince by Saint-Exupery. Mais bien sûr!) So why do some classics survive, while others do not?

In some cases, it is a matter of language. Authors like Conrad, like Hemingway, stand the test of time because they do not load their books with adjectives and adverbs (rather the reverse, in dear old Ernest’s case). Nouns and verbs are less sensitive to fashion than descriptive words, so if the text mostly consists of texts and nouns, the language remains relevant, vibrant even.

But what all those timeless books have in common is something else. It’s all about the people, peeps. There’s a reason why Elizabeth Bennet and Mr Darcy still enthral new readers, despite the story being reasonably predictable and not exactly high-paced. Anna Karenina’s infidelity, her subsequent humiliation and despair still moves us, as does Jane Eyre’s depressing childhood and the terrible blow her pride (and love) suffers when Mrs Rochester numero uno is revealed. (In Jane’s case, though, I suspect it is that final line which sort of clinches it: “Reader, I married him.” Perfect.)

For well over a century, the Nobel committee has awarded authors the Nobel Prize in Literature for their contribution to the global literary canon. When I read through the list of the prize winners during the first fifty years, I suspect very, very many have already become obsolete. Seriously, how many have read Prudhomme? Benavente? Maeterlinck? Writer like Pearl.S.Buck are almost forgotten (more’s the pity in her case. The Good Earth is quite the read – but yes, it is dated) while others, such as Kipling and Undset still attract readers. Once again, because of the characters. We can still relate to Mowgli and Kim, and as to Kristin Lavransdotter, show me any woman in the world who can’t relate to her and how she faces up to what life throws her way.

Obviously, fabulous characters and no plot does not a story make. Readers tend to pick up books because they want to be told a story, they want to be transported elsewhere, hastily turning pages as they are sucked into the plot. The conclusion, therefore, is that it’s people and plot. But plot without people will never work. Never. Books with people and little in the way of plot can work. Sometimes. This is why a book like Fifty Shades of Grey—which we all “know” is terribly, terribly written, full of clichés and with awful dialogue (does ANYONE say “Whoa!” while in the throes of passion????)—sells millions and millions. Whatever else she may do wrong, E L James does one thing right: she gives the readers the people they want, in this case a very young but very mature and compassionate young woman who can take on and tame the angry, wounded beast that is Mr Grey. It’s the classic fairy tale of the good girl penetrating the layers of evil that shroud the beast to tap into his golden heart. Supposedly, she also writes hot sex scenes. Not so much, IMO. Once again: it doesn’t matter. What matters is that millions of readers care about Christian and Anastasia. Just like millions and millions (if we count since it was first published) care about Elizabeth Bennett and Mr Darcy. Or Jane Eyre and the deliciously haunted Mr Rochester. Or the little prince and his rose, that rather vain and self-engrossed flower the little prince so loved.

I’m guessing none of the above comes as a surprise –neither for writers or readers. But I’d love to hear which classics you feel have stood the test of time and which have not. And while you mull that one over, I’m going to dig out my very old, very loved copy of Le Petit Prince. As always, I’ll laugh at the picture of the boa which has swallowed an elephant. As always, I will feel my chest constrict as we get to the sadder parts. Because that’s what all great classics do: they make us feel, they make us share in the pain and joy the characters experience, thereby making us grow (a bit) as people.

I’m guessing none of the above comes as a surprise –neither for writers or readers. But I’d love to hear which classics you feel have stood the test of time and which have not. And while you mull that one over, I’m going to dig out my very old, very loved copy of Le Petit Prince. As always, I’ll laugh at the picture of the boa which has swallowed an elephant. As always, I will feel my chest constrict as we get to the sadder parts. Because that’s what all great classics do: they make us feel, they make us share in the pain and joy the characters experience, thereby making us grow (a bit) as people.

Was he a perfect king? I suspect the French would have replied with a resounding NO. After all, Edward III unleashed the Hundred Years’ War on France, resulting in far too much death, too much loss. He was ruthless in war—whether in France or Scotland—but he was also a man determined to act honourably towards his vanquished foes. Well…if it suited him politically.

Was he a perfect king? I suspect the French would have replied with a resounding NO. After all, Edward III unleashed the Hundred Years’ War on France, resulting in far too much death, too much loss. He was ruthless in war—whether in France or Scotland—but he was also a man determined to act honourably towards his vanquished foes. Well…if it suited him politically. “Who is she?” Matthew asked, peering over my shoulders.

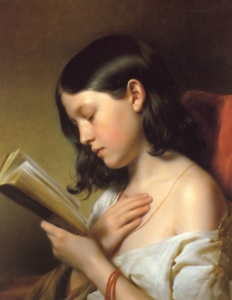

“Who is she?” Matthew asked, peering over my shoulders. The other day, I was feeling a bit wilted around the edges. Best cure for that is to curl up somewhere and escape into a book. Quite often, I’ll opt for a book set in the past, one of those books that combines blood and gore with courtly love and honourable men (like my own books, come to think of it. But I cannot read my own books to escape: I end up using a red pen and doing further corrections…)

The other day, I was feeling a bit wilted around the edges. Best cure for that is to curl up somewhere and escape into a book. Quite often, I’ll opt for a book set in the past, one of those books that combines blood and gore with courtly love and honourable men (like my own books, come to think of it. But I cannot read my own books to escape: I end up using a red pen and doing further corrections…) Ms Day does write historical romances – quite adeptly, I might add – but it is her Crossfire books that I return to time and time again. A male protagonist burdened by his past encounters an equally scarred young woman. Sparks fly, and just like that, Eva and Gideon grow into my heart. Eva is no retiring violet – but her past haunts her. It is Gideon who saves her from her past, and she in turn takes on the task of freeing this man from the shadows of his childhood. Two damaged people trying to heal each other – a somewhat combustible combo, all of it delivered in well-paced prose, generously laced with hot, steamy sex scenes.

Ms Day does write historical romances – quite adeptly, I might add – but it is her Crossfire books that I return to time and time again. A male protagonist burdened by his past encounters an equally scarred young woman. Sparks fly, and just like that, Eva and Gideon grow into my heart. Eva is no retiring violet – but her past haunts her. It is Gideon who saves her from her past, and she in turn takes on the task of freeing this man from the shadows of his childhood. Two damaged people trying to heal each other – a somewhat combustible combo, all of it delivered in well-paced prose, generously laced with hot, steamy sex scenes. None of the above crosses my mind when I retreat into my escapist bubble. In my bubble, all I want is to be entertained, dragged out of my reality which, at present, sucks. Any writer who can create an illusion strong enough to yank me out of the here and now has, IMO, done their job. Kudos to them, I say.

None of the above crosses my mind when I retreat into my escapist bubble. In my bubble, all I want is to be entertained, dragged out of my reality which, at present, sucks. Any writer who can create an illusion strong enough to yank me out of the here and now has, IMO, done their job. Kudos to them, I say.